When Orion Samuelson was approached by chancellor earlier this year about delivering a commencement address at the University of Illinois in May, he did a double-take.

“I said, are you sure you have the right phone number, are you sure you have the right person? Because I had no idea of ever reaching that level of speaking,” Samuelson said.

Orion Samuelson stands with Chancellor Phyllis Wise of the University of Illinois during the school’s graduation ceremonies on May 31. Samuelson was the afternoon commencement speaker. (Photo provided)

Samuelson, who does about 40 public speeches a year ranging in scope from local chambers of commerce to an acceptance speech at the National Radio Hall of Fame considered a university commencement address a special honor.

Though he usually leaves room for improvisation in public speeches to keep them fresh, Samuelson thought a well-tailored message should be the speech’s central focus. The circumstances of the speech also presented a challenge.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, the last thing a college graduate wants at commencement time is to sit through a speech; they want to get out of there, so what do you do?'” he said.

A current project of Samuelson’s provided just the creative spark he was searching for.

“I got to thinking, I’m writing a book, but everybody writes a book. The minute [you] arrive on the planet, you start writing a book: your book of life,” he said.

And there it was. Samuelson would suggest new chapters for these students to add now that their current one was ending.

In his speech, Samuelson recommended that chapters of students’ lives be devoted to: education and technology, their dreams, bumps in the road, places they want to go, and things they want to do outside a career, and most importantly, family.

These tips and lessons were harvested from both Samuelson’s nearly 60 years in broadcasting and his beginning as a cow-milking farm boy from Wisconsin.

For example, one of Samuelson’s mantras, “never evaluate a happening until after it happens,” is one that may have been utterly rejected by Samuelson in his youth.

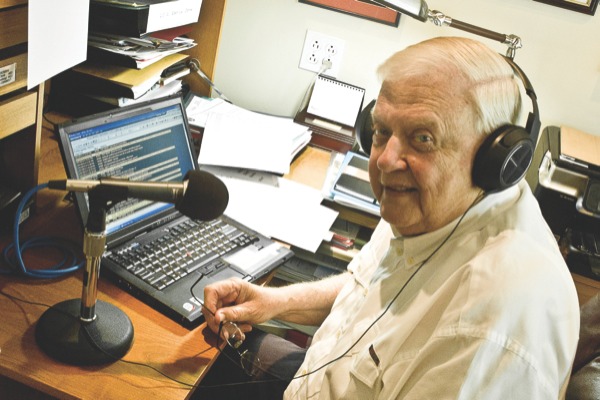

Samuelson poses in front of his home broadcast equipment. Samuelson is able to perform some afternoon updates for WGN radio from his Sun City home. (Photo by Mason Souza/Sun Day)

Before his freshman year of high school, Samuelson developed a bone disease in his leg that left him unable to do the things he loved, like basketball, for two years.

“I was mad at the world because, my God, two years are taken out of my life,” he said.

But it was those two years that would change Samuelson’s life in the best way imaginable. It was then that he started listening to radio, really listening and hearing his future through the airwaves.

With his newfound focus, Samuelson would attend the American Institute of the Air in Minneapolis, which gave him the foundation to start a career in radio.

Starting out in a small station in Sparta, Wisc., Samuelson developed his style and found his niche in agriculture. His formula of excellent grammar, enunciation (developed because his voice competed with machinery for farmers’ ears), and that booming voice earned Samuelson the spot as farm service director for WGN and host of “National Farm Report.”

As a young man, Samuelson wanted to be in radio partly to get out of having to wake up at 5 a.m. to milk cows.

“Now I get up at a quarter to three in the morning to do a program for people who get up to milk cows,” he joked.

That attitude towards work – Samuelson said he’s never worked a day in his life, because he loves what he does so much – was another key point he passed on to graduates.

Despite his 52-mile commute to WGN studios in Chicago, Samuelson has not lost scope of the long journey from farm worker to farm services director.

It’s a path that has taken him to 43 countries and allowed him to meet seven presidents.

The impetus behind Samuelson’s success is best summed up in another point of advice he gave graduates – one that is also the title of his upcoming book.

“You can’t dream big enough.”