An Angel on my Shoulder

Driving on moonless nights in combat can be very stressful. Turning on one’s headlights was a court martial offense. An experienced driver had tipped me off to the fact that one could still manage by not looking directly ahead; but up and to the right; nevertheless it was still a harrowing experience.

My sergeant told me we were going to reconnoiter an advance position that our company may be moving to. He had two corporals with him and we were going to check out a mountain top. When we approached the mountain he told me to shut my lights off. I asked him if I could keep my dims on and he said “no way!”

The narrow road up was steep and had been carved out of the side of the mountain wide enough for one vehicle; fortunately it had a small clearing every so often so a driver could turn around if he had to. My sergeant told me to take it slowly. I picked up speed in first gear, going five miles an hour at the very most. I couldn’t see the mountain on my right at all, everything was completed shrouded in darkness as we wound around the mountain four complete cycles when suddenly I heard a thundering noise. The ground shook as if it were an earthquake. Someone screamed “what is that!?”

I floored the accelerator, wanting to distance myself from the terrible noise. In panic I realized I could drive off the mountain. I jammed on my brakes, the jeep slid and came to an abrupt stop and then the front tires dropped over the edge of the cliff. A gigantic tank came rumbling down the road past us, narrowly missing us by inches. The corporal sitting in the rear could have reached out and touched it as it rumbled past. The sergeant’s voice was trembling and he ordered everyone not to move as he gingerly got out to check our plight. The front tires were off the cliff and we were close to teetering off the edge. He told one of the corporals to get out slowly and grab the back bumper and then the second man got out and did the same. I put the jeep in reverse and all three of them pulled the jeep back on the road while I sat at the wheel and slowly accelerated in reverse.

I turned around; they all got in and we took off for base camp. The sergeant stated that there had been a massive blunder; someone in charge had failed to notify the tank crew that we were coming up. For an oversight like that we could have been crushed like pancakes or driven off the side of the mountain by the tank. He told me to head home; he couldn’t take a chance that another tank may be coming down. I was elated to be leaving.

Not a word was spoken all the way home; there was an eerie stillness with each man deep in thought of what had just happened. When we arrived back in camp the two corporals took off quickly without saying a word. My sergeant walked behind them but suddenly stopped and came back to my jeep and sat down with me. He said he had to ask me a question.

“Did you really see that tank coming and what made you go in the direction of the turnaround?” I told him that was two questions but I would answer them.

“I didn’t see that tank and I went in that direction because the angel on my shoulder took over, I didn’t see any turnaround.” I told him that I went to a psychic once and she told me I have an angel on my shoulder This incident proved she hadn’t lied. He just shook his head in amazement and walked away. I quit driving a week later and went back to my recoilless rifle squad. I concluded that driving a jeep in combat was not all that it’s cut out to be.

By Jerry Goldberg (Neighborhood 13)

Driving and Swearing

When we first arrived in Korea, we were lined up in a single file for as far as the eye could see in front of the Captain’s tent, waiting our turn to be interviewed. I snapped to attention and saluted when I faced the Captain. He stood up and saluted and said, “At ease!” I was far from being at ease, but he looked at me and asked what I wanted to do while I was in Korea. I told him my M.O. was rifleman, and I didn’t understand the

question. He wanted to know if I had special skills when I was a civilian. I told him I was a plumber. “Ah, a plumber. I’m sorry but we have no need for plumbers here.” He asked me if drove a truck while I was doing plumbing, and I told him I did. “Fine, when the new Jeeps arrive, you shall be E company commander’s official chauffeur. We’ll let you know.” He asked me if I could drive a larger truck. I lied and told him I was an expert. He said I would drive the larger truck in convoys until my Jeep arrived.

Can you imagine the elation I felt? No more slogging through the mud like a common grunt. I had moved up a notch. I kept it a secret from the others, but I was brimming with excitement. I asked my closest friend if driving a 6X6 truck was difficult. He said it wasn’t easy, because you had to downshift while going down steep hills and it could be a little tricky. That’s when I got my first gray hair.

Upon arriving at the motor pool, I was shown my truck. It was a monster. I had to oil, grease, and maintain it. I had never looked under a hood before, and I couldn’t believe how busy it was. Maybe this was a bad idea, but I felt I had to stick it out until my new Jeep arrived because my options were limited.

My first convoy was a nightmare. I had to follow the truck in front of me. Not too close, but at the same time, not too far away. We had to maintain that interval in case of incoming shells. Unfortunately, I was near the rear, and it was murder keeping up. Being summer, the roads were unbelievably dry and dusty. All I could see in front of me was a giant cloud of dust. When I had to shift, the gears sounded like they were going to pop out one at a time. If I had a flat tire, I didn’t even know where the jack was. The seat itself was adjusted for a giant, and my toe barely reached the gas pedal. No air conditioning of course, and when I rolled the window down, I choked on the dust. This was no fun at all, but somehow I made it all the way there. Oh yes, they told me to be careful of land mines when turning my truck around. A few drivers had been blown to smithereens when they got out of the track of the driver in front of them. My second gray hair sprouted.

When they told me my new Jeep arrived, I was so elated I wanted to cry. The other drivers who drove were so jealous they turned green with envy. They had beat-up Jeeps and mine was brand spanking new.

Life was good again, but only for a while. Driving the Lieutenant was fun. He was from Wisconsin and he enjoyed my humor and I enjoyed his company. One problem though…where to sleep? A tent was out of the question because everyone was in bunkers, and I was odd man out because I was no longer a rifleman. I had a problem. I slept on the back seat, the front seat, and even the hood of the Jeep. When I woke up on cooler mornings, I had trouble straightening up. I didn’t have to worry about sleep too much, because they were always waking me up in the middle of the night anyway.

I did have a knack for finding scarce commodities, though, and when the word got around, the Captain took advantage of it. They would wake me up and tell me to get the Captain some cheese, salami, chocolate, or other delicacies. Water was scarce, and when he got thirsty, it was my job to find it. They didn’t care if I had to dig a well. One time I drove 30 miles in the dark to find water. I ended up in an adjoining Turkish camp trying to convey in frantic sign language my need for water. The Turkish major in charge finally understood my posturing and told his corporal to fill up my five gallon can with water from the fish pond.

What if my Captain swallowed a goldfish? I didn’t want to offend the Turk, so I went a short distance, stopped the Jeep, and dumped the water. I felt guilty about the fish.

When I returned, I said to the Captain’s orderly, “Sorry, no water. If they want to line me up in front of a firing squad, I’m ready.”

“Don’t worry about it; the Captain is like a pregnant woman, and he’s forgotten about the water, he wants C-rations now.”

When it rained, the unpaved roads became quagmires. Sure, the Jeep had four-wheel drive, but when the rain came in torrents, 12-wheel drive wouldn’t have helped. Once I was driving with another Jeep driver in front of me, and the road was completely washed out. He stopped and asked me if we should try to cross it. I told him we had no choice. I would go first. I backed up to give myself room and then floored the accelerator. I was almost airborne, and when I landed, my foot came off the gas pedal and the Jeep sank deep into the mud. I tried rocking the Jeep. If it had a voice, it would say, “Are you kidding?”

There were a group of South Korean laborers walking down the road, and I motioned for help. They lifted the jeep and put it on solid ground. Suddenly, I heard the whine of a mortar shell, and the Koreans scattered. The enemy had probably been watching this whole fiasco. They didn’t want to waste shells on a lone driver, but when they saw a bunch of victims congregated together, they couldn’t resist. The other driver didn’t want to take a chance on getting stuck, ran in my direction, and dove in my open door as I took off.

I envied the riflemen because they had nice, comfortable bunkers, and they envied me because I didn’t have to slog on foot through the mud. One soldier by the name of Clyde was so jealous of me driving a Jeep, he needled me unmercifully. One day when I reached my limit as far as my needling quotient was concerned, I approached him.

“Clyde, I have good news for you.” He looked at me quizzically, wondering what was coming next. “You expressed a desire for my job; if you are willing, I shall recommend you for it because I’m retiring.”

Clyde’s eyes widened in surprise, and he asked me if I was joking. “I’m serious, you wanted to drive; I’m going to recommend you for it.” I think he wanted to hug me, he was so elated.

Next day, I approached the Captain. I told him I no longer wanted to drive. He asked me my reason, and I told him I missed my recoilless rifle squad and I needed to be with them. He asked me what he was going to do for a driver, and I told him I had one picked out for him, and I gave him Clyde’s name.

I didn’t see Clyde for a few weeks, but when I did, he looked pathetic. His eyes were rimmed in black from lack of sleep and he looked gaunt and haggard.

“How you doing, Clyde?” I asked, trying to suppress the inner joy I felt.

“Don’t ask,” he responded with a dour look. “I am asking,” I said, not wanting to ease up.

With his head down, he responded, “I haven’t slept in two weeks.”

“Oh, are you saying the job is harder than you thought it was?”

“Are you joking, driving a Jeep in combat is a nightmare.”

“Well good luck with that, Clyde; I just wanted to hear that from your rosy lips.”

By Jerry Goldberg (Neighborhood 13)

Distinguished Flying Cross No. 1

During one of many fighter sweeps south of the large Japanese base at Rabaul, New Guinea, heavy anti-aircraft appeared to be coming from a point just south of a large well-marked Red Cross building. Geneva Convention rules prohibited hitting hospitals marked such as this, even in enemy territory. With his wingman, Fen determined they could drop their 500 lb. bombs south of the hospital to knock out the Japanese AA battery.

Diving down at 400 mph, Fen released his bomb, but it fell short by a few hundred yards and struck the southwest corner of the building. Fen and his wingman quickly climbed out of there, shells flying all around them, and looking back from 10,000 feet, “They saw a fantastic series of explosions with flame and smoke almost reaching to their altitude.” The entire Red Cross “hospital” was a major Japanese ammo dump, and due to the inaccurate bomb drop, multiple explosions were seen for hours, with smoke rising to 20,000 feet as later flights reported.

After returning to base, but before debriefing, both pilots decided the less said the better. An Australian coast watcher, evidently in the area, later sent congratulations through channels. Those brave coast watchers, hiding and dodging Japanese patrols, radioed constant enemy activities to our intelligence network.

Over a year later while based at Page Field, MCAS, Parris Island, Fen was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross for “meritorious action against the enemy while in the Southwest Pacific campaigns” with no particulars of any kind stated in the citation. Fen was sure that the wayward-bomb drop was the occasion.

Distinguished Flying Cross No. 2

Early in 1945, while providing joint air cover (U.S. Marine Corps & Army Air Corps) for the Allied Invasion Convoy moving up from the southern Philippines to the Lingayen Gulf, our “on station” assigned air time was four hours, and we were then to be relieved by Army Air Corps airplanes for their four-hour stint. The split operation consisted of eight Corsairs from our squadron, and the same number from the Army Air Corps, who flew P-51s. We were under the direct control of the Navy Convoy Admiral Commander, and under strict orders “not to chase” after enemy planes unless they began an attack on the convoy. Some were sighted, but kept their distance, as were submarines, but the convoy’s destroyers fanned out and kept them at bay.

It was a very boring mission, eyes straining while we weaved back and forth at a reduced speed to conserve fuel for our return to base. Our four-hour assignment passed, but no P-51s came to relieve us; something or someone had messed up. Only two hours of daylight remained, and the convoy was still vulnerable to enemy air attack. After checking with all our pilots on remaining fuel, our Division Leader, Jim Craddock, informed the convoy commander that we would remain on station, “for no longer than two hours, otherwise our tanks would make good flotation gear.”

Darkness arrived on schedule, and the grateful convoy officer thanked us and released us from station. Halfway into our return flight, we were informed our base was closed due to inclement weather. Mindoro, an additional 30 minutes northwest, was given as a landing possibility; however, there was a problem. Base control didn’t know if Japanese or guerrillas controlled this only landing strip since it changed hands fairly often. With our gas soon nearing fumes, we had no choice. Navigating to a strange airstrip on a dark night was dicey, but we found it.

Our Division Leader, Jim Craddock, dragged the strip at 500 feet, spotted the flares put out by the friendlies, and gave us the okay to land. He then peeled off to the left at about 300 feet into his turn, went straight down and impacted into flames, lighting up the entire area. It was an overcast, black night with no visible horizon and vertigo was the logical culprit that caused Jim’s crash. Seven of our squadron landed safely. Fuel for our planes arrived later in the morning, and we flew back to base, sorrowfully sans Jim.

The Navy Convoy Commander recommended we receive citations, and we all received U.S. Marine Corps Distinguished Flying Crosses and Jim Craddock received a U.S. Navy Distinguished Flying Cross.

Fenwick E. Lind,

Retired fighter pilot captain USMC, WWII

Lind passed away in 2012, but his story is submitted by his wife, Theresa.

Why Did the Sergeant Follow the PFC? (I was the PFC)

During the war in Germany, our platoon went on a patrol in the middle of farm fields to determine if there were any Germans in the area. We scattered, dug our foxholes, some sleeping while others kept guard. We heard a German motorcycle, and since it was getting light, we decided to go back to our lines. We couldn’t locate two GI’s and had to leave without them. That night while we were there, it snowed about 10 inches, covering all our landmarks. Our Sergeant thought he was leading us back to our lines, but I thought that was wrong and told him so. I left to go another way, and the whole platoon followed me. I hoped I was correct. After about an hour, we noticed a knocked-out German tank which had been there when we first arrived in the area. I knew then we were on the right track to get back to our company. When we arrived, we were questioned about the two GI’s left behind, but after an hour, they arrived and asked why we had left them. They said they found their way back by following our footprints; however, they could have been German footprints!

Paul Souchek,

Sergeant, 36th Division, 143rd Regiment. U.S. Army

Neighbors

Next year will mark the 60th anniversary of the start of the Korean conflict (which parallels our involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan in some ways). The U.S. was sure it would be victorious within a short time (the troops would be home by Christmas). The Chinese would not risk involvement, which would escalate the conflict. This “reliable” intelligence proved to be grossly mistaken.

Though it was never a declared war but always referred to as a police action for the United Nations, then Commander-in-Chief, Harry S. Truman, believed U.S. intervention was necessary to prevent the Communists from seizing the entire peninsula. On June 25, 1950, the president announced he was sending troops to the area.

My neighbor, Alan Terrill, just 19 and working in his family’s restaurant in New Jersey, had no idea how much or how quickly his life would change. Previously enlisted in the Marine Reserve, he received notice in early July his services were required and reported for active duty, then sent to Camp Pendleton, CA, for very short basic training (four weeks) with the 1st Marine Division. By October he was on a ship bound for Korea and in late November was engaged in the most savage battle of Korea Americans experienced; they had been ordered to push to the Yalu River and drive the North Koreans from the country. The military considered it a vital necessity to end the war. The “police action” battlefield conditions became fierce with the weather: harsh, bitter cold and unrelenting over extremely rough terrain.

The Chinese had moved 120,000 seasoned army volunteers across the Yalu undetected, and they struck with full force beginning November 27 against the X Corps’ troops made up of the 5th and 7th Marine Regiments at the Chosin Reservoir and the Army Regiments east of the Reservoir. These young marines and soldiers endured extreme hardships, from the sub-zero weather, the mountainous terrain, and the Chinese in overwhelming numbers. It is a remarkable tribute to the quality of units reconstituted only three months earlier, heavily manned by reservists, that they mounted so determined a defense under these appalling conditions.

Even though marines found themselves greatly outnumbered, each morning they were still holding their positions. After a brief discussion among the American high command about continuing their own offensive, it was apparent to the marines their predicament was precarious and had only one option open: withdrawal to the coast. When a reporter impolitely referred to the withdrawal as a “retreat,” a general corrected him, pointing out that when surrounded there was no retreat, only an attack in a new direction. The press improved the general’s remark into: “Retreat, hell! We’re just attacking in a new direction.” The breakout from the Reservoir to the coast and the waiting troop ships was 78 miles, over a frozen single lane road and took 14 days with fighting the Chinese all the way.

There were a host of tragic spectacles, so many acts of heroism. I will only recount one I found particularly touching. In the chaos that followed, men became lost from their companies without weapons or equipment. A young Army solider was in this predicament when the Koreans captured him. Marched for several days until numb and at the limits of exhaustion, the young soldier sat down on the running board of an American truck. He could not bring himself to move when a Korean guard ordered him to his feet. He was hit twice, hard, on the head and passed out. When he came to, he was alone, probably left for dead by his captors. For what seemed to be hours, he stumbled around, unable to walk on his frozen feet, until he somehow found his way back to the lines. He finally met a “big ole Marine colonel” who carried him to a truck and unto an aid station, where he was flown to Japan for treatment.

Alan has kept meticulous records of his experience, writing many letters to his mother, who miraculously preserved them for posterity. He has books, movies, and so much information collected over the years, I don’t think he’d mind being called a “walking encyclopedia on Korea.” It is a wonderful account, but lacks the twelve-day period he was engaged in the battle of the Chosin Reservoir and the march to the sea. He tells his mother he doesn’t want to go into the details in a letter, but will fill her in when he is home. All he will say is that he suffered some frostbite on his toes and considered himself lucky to come out of it without a scratch. He served until being honorably discharged in April 1952 and resumed his life like so many others during the era, expecting no special consideration. He was simply doing his duty.

Though some 36,000 Americans would die to protect the freedom of South Koreans, Alan doesn’t believe Korea is the forgotten war. Instead, he sees it as a forgotten victory that stopped the flow of Communism and is rightfully proud of being a Marine and serving in a conflict for his country. So the next time you wave to your neighbor, why not try and find out a little more about them. We are glad and grateful we had men like Alan Terrill, as well as the men and women today who are trying to stop the flow of terrorism in foreign lands.

By Betty Reffke

Christmas in Vietnam with Bob Hope

During Christmas of 1965, I was in the Army stationed at Nha Trang Vietnam. A few days before Christmas, our platoon was told to install rolls of barbed wire fencing around some buildings off the base. Bob Hope, Ann-Margaret, Joey Heatherton, and their entourage were going to be spending one night in these buildings while appearing here for a Christmas show for the troops.

A few days prior to Christmas, we were told a temporary truce had been called, and we had to turn in our weapons to be locked in a conex for a few days. The reason for this was that during the truce, the Red Cross was coming in Christmas Eve day with goodie packages and beer for the troops. They felt beer and weapons were not a good combination. Everyone was allowed two beers, but many trades were made. Some didn’t want beer, but rather an extra goodie package.

Some of my buddies and I wound up with quite a few beers, something we hadn’t had for six months. Sleeping very soundly in our tents after those beers, we were awakened by the sounds of explosions and shrapnel hitting our tents. Taking cover in a bunker, we could see the flash of weapons being fired in the pitch black of night. It ended fairly soon, but unfortunately there were a few casualties.

The next morning the USO cancelled the upcoming Bob Hope show fearing another attack. Later in the day, word came down that Bob Hope insisted on doing the show, and the USO relented. Troops were flown in and trucked in for the show, including some from hospitals. The front rows had guys in wheel chairs, some with IVs attached. For a few hours that day, everyone forgot about the war, death, injuries, and being away from home on Christmas. The show was terrific and ended with everyone singing “Silent Night”; there were few dry eyes to be seen.

Bob Hope entertained the troops over many decades and wars. For him and his entourage to give up their holidays at home and travel thousands of miles to a risky environment with accommodations less than pleasant to entertain troops is a real tribute to what kind of person he was. Thousands of troops had a better Christmas every year because of him. What a guy.

John Diebold, Neighborhood 17

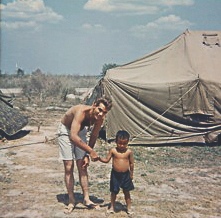

Cu Chi South Viet Nam, Feb. 1967

This puppy and little boy were all we found after the Viet Cong wasted the village for being friendly to army troops. I wish the protesters could have seen this.

Remembering 50 years ago

In October of 1962, I was en-route to the 502nd Administration Company, 2nd Armored Division, Fort Hood, TX. At that time, President Kennedy initiated the blockade of Cuba and what was known as the Cuban Missile Crisis occurred. Upon arriving at Fort Hood, which was now on full alert, we were issued weapons, combat gear, and told to pack our civilian clothing. We remained on alert for approximately three weeks until a UN agreement was reached. We then continued our role of “Cold War” soldiers.

In summer of 1963, a plan was pushed forward to see what it would take to move a combat division to Europe in order to re-enforce our allies. It was entitled “Operation Big-Lift,” and you guessed it – the 2nd Armored was the division to go.

13,000+ men and their combat equipment were airlifted to Germany. The tank companies, artillery, and infantry picked up the heavy equipment stored in Germany and proceeded to maneuvers. The 502nd Administration Company was assigned a permanent location and spent the next 30 days in tents in a forest near Kaisersaulten, Germany. Other than for the rain, the fall weather was beautiful, but the Tent City left a bit to be desired. No running water and no indoor plumbing.

Shower runs were twice a week at a nearby Army barracks, and our latrine was located approximately a quarter mile down from the camp. As you can see in the picture, we had a “Deluxe Eight-Holer.” When the engineers who built it were asked why there was no roof, they said they ran out of lumber. We didn’t quite believe that. Would you have?

It did prompt you to get your business done quickly and as the structure began to weather due to the rains, made you check for splinters.

We made the best of our situation, had a lot of laughs, took some photos, and enjoyed our time in Germany. The picture shows part of my squad taking a break on the “Eight-Holer.”

The maneuvers ended, and we returned to Fort Hood in the early hours of Nov. 22, 1963. The orders were to have all Administration Operations up and running by 1700 hours. After a few hours of sleep, we got to our jobs, and in the early afternoon, we heard the announcement of the assassination of President John Kennedy. As with most people of my generation, I can remember exactly where I was: In the 502nd Administration Office Building, wondering what our role will be now.

As usually happens, an orderly change transpired and life continued on in its usual manner. My tour of duty was up in August, 1964, and I came back home to family and friends. I never saw any combat actions, but had a number of experiences I will never forget.

So on this Veteran’s Day, to all of my comrades-in-arms,

Those that served before me,

Those that served with me, and

Those that served after me;

I salute you!

Jerry Cieciwa

Sun City

Memories of the Vietnam Conflict – The Best three minutes of my life

I was stationed in Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, with the Army 54th General Support Group in 1971. Cam Ranh Bay was a major supply base for our troops. Much of the fuel for military vehicles and aircraft was piped into huge storage tanks on an area of Camh Ranh Bay that we called the “tank farm.” Thousands of gallons of mogas (gasoline), diesel, and JP4 (jet fuel) were stored in an array of storage tanks. Five thousand-gallon tankers would then draw the fuel from the storage tanks to supply vehicles and aircraft in their units. The tank farm was guarded 24 hours a day by our troops. However, one night under the cover of darkness, enemy sappers cut through the guard wire and crawled into the tank farm setting satchel charges with explosives to many of the storage tanks. I was not on duty that night, but I remember being awakened by huge explosions and one of my fellow soldiers screaming that the tank farm had been blown up. The sky was as bright as day from the burning fuel. We spent the rest of the night guarding what was left of the fuel dump and searching for the sappers who were long gone by then. Several of the guards on duty were killed in the explosions, and their posts burned to the ground. The melted storage tanks burned for several days.

In 1971, communications were not what we have today. The Internet didn’t exist then, and letters to home would take at least seven days. Of course the media reports were very timely. My wife, Sue, had been visiting with my mother when the news about Cam Ranh Bay was reported on TV. I can’t imagine the anxiety they went through not knowing that I was OK. I was fortunate to learn about a short wave radio hookup that a Navy detachment had set up on the other side of the Cam Ranh base. Those guys were pretty creative. They had set up what they called a MARS station that linked a series of radio operators across the islands of the Pacific to the U.S. west coast. They were able to connect the radio transmissions to land-based telepones in the U.S. so that soldiers would be able to communicate with loved ones back home. The calls were limited to three minutes so they could get many of the troops connected, but it was the best three minutes of my life to be able to tell Sue I was OK and not have her wait another seven days to read about it.

Captain Don Grady

Sun City