John Throckmorton’s father’s WWII dog tags returned 65 years after his death through efforts of Dutch students Ivo Wilms and Bart Moonen

SUN CITY – Could you ever imagine that a fallen American infantryman, a tiny metal tag, 65 years of time, a generous Dutch archaeologist, and a retired Sun City management consultant would all come together to tell one of the most unbelievable and heart-warming stories of World War II?

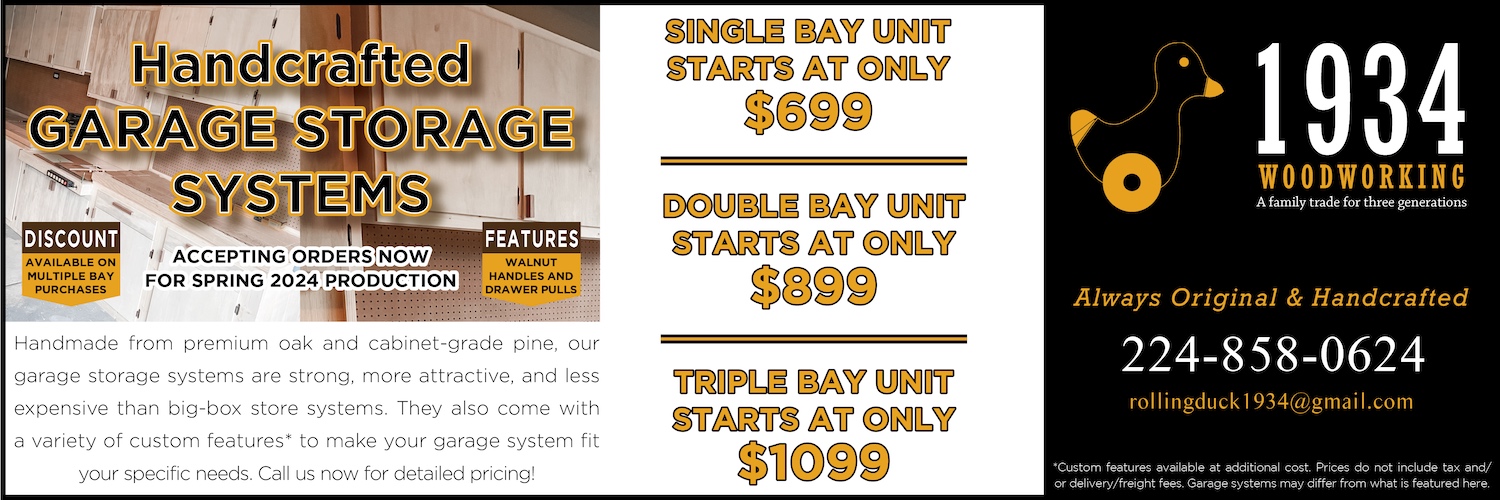

John Throckmorton (center) poses with Ivo Wilms (left) and Bart Moonen, (right) the Dutch students who recovered his father’s lost dog tag. (Photo Provided)

The storytellers are Sun Citian John F. Throckmorton and Bart Moonen, a young Dutch archeology student who likes to collect lost military items and return them to their owners.

This story begins in Chicago in October, 1944. John Elder Throckmorton, young John F.’s father, was home on leave after basic training. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in April of that year.

“I was three years old the last day I saw my father, when he came home on leave,” young John recalled.

His father was shipped to England soon afterward. Despite his paratrooper training, he was assigned as a replacement in the 94th Infantry Division, a part of Gen. George Patton’s Third Army. He arrived in continental Europe on Feb. 1, 1945, and became a member of the division’s 301st regiment.

The 301st went into action in mid-January in the Saar River Valley in Germany, just north of its border with France. John E. and his unit quickly became involved in some of the heaviest and fiercest fighting of the war. Desperate German units fought hard to protect their homeland from the allied invasion. American units were just as determined to be the first to break through the famous Siegfried line, beat the Russians to Berlin, and end the war.

(After the war, the 94th Division became famous for helping the Third Army defeat the Germans in the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium in December, 1944, and for being the first American unit to reach the Rhine River in Germany in March, 1945.)

On Feb. 28, 1945, John E.’s unit was sent on a patrol in the Neunhauser Wald (forest). Amid heavy fighting, he went missing, and his family was notified. The 301st regiment and 94th participated in many more major engagements until the war ended on May 7, 1945. Later in May, John’s body was found – among those of many other fallen Americans – in the same forested area.

Only one of John’s two dogtags was recovered in an inventory of his personal effects, however. His family was notified that he had been killed in action. He was buried in an American military cemetery in Lorraine, in northeastern France. About this same time, John E.’s family was also notified that John E. was awarded the Bronze Star, one of the military’s highest honors, for “exceptional service and high valor,” while serving in Germany.

Shortly afterward, young John’s mother moved her family from Chicago to Lawrenceville in downstate Illinois, her hometown.

“I went on to pursue a career in business,” John F. said. “I worked for a large Chicago-area company as a management consultant. I married my wife, Martha, and we raised four daughters in Glen Ellyn, Illinois.”

Fast forward over 60 years to a few years ago, back in Europe. Enter Bart Moonen, a young Dutch senior archeology student and military history enthusiast, along with his friend and fellow student, Ivo Wilms.

“A few years ago, I went on vacation with my parents to the town of Saarburg, a picturesque, medieval town on the Saar River in Germany,” Moonen said. “I had already developed an interest in World War II through stories my grandparents told me. I obtained a metal detector that I used to find remnants of the war and went online to see if anything happened in the vicinity of Saarburg. I discovered that this was the 94th Infantry Division’s bridgehead across the Saar River. During the vacation, I found my first .50 caliber casings and a piece of a German belt buckle. This is what got me interested in the region.”

Moonen met German citizens who helped in his research and even offered him accommodations in their homes during his excavations.

“In 2010, we came across some items that were named or had numbers scratched on them, and I started retracing them so I could return them to families or the veterans themselves,” he said. “This is how I came into contact with the 94th Infantry Association.”

By coincidence, the Association conducted a battlefield tour that year, and Moonen guided it and made several American friends.

He and Wilms continued to spend considerable time in the Saar region, conducting semi-professional approved digs and finding shell casings, helmets, canteens, coins, and other military artifacts.

“Even today, there are many bunkers, foxholes, shell craters, and trenches visible in this forest,” he said. “In October, 2011, we discovered some old foxholes on a gentle slope where I got a signal from my metal detector. I thought it would be another shell casing until a shiny piece of metal flew off my shovel. I immediately ran over to Ivo to show him what I had found.”

It was an undamaged and shiny U.S. Army dogtag with the name, “John E. Throckmorton” engraved on it – the missing dogtag from young John’s fallen father.

Online, Moonen discovered John E. was part of the 301st regiment and had been killed in action on Feb. 28, 1945. Further investigation revealed John E. was originally from the Chicago area, but Moonen met a dead end from there. He then asked a friend in America to request information from the U.S. Department of Defense. Eight months later, in June, 2012, the request was processed.

“I learned that John E. was killed by a mine and that his body was found in a coordinated U.S. military search some distance from where I found the dogtag,” Moonen said. “This has led me to believe it may have been lost by one of the grave registration members when they were working on another body. From the file, I also learned that John E. was married and had a son named John Ford Throckmorton in Illinois.

“Through the Internet, I found a John F. Throckmorton from the Chicago area with the correct age living in Florida (John and Martha own two homes, the Florida one is in Ocala.) “I called there but got no answer.”

“When we first heard about this, we thought it was a scam,” John F. said. “We just blew it off. As Bart was trying to reach us, my daughter, Jean Puyear, was online seeking information about her grandfather and saw a post about two people that found John E. Throckmorton’s dogtag and were trying to get in touch with his family. She discussed it with a researcher friend, who told her it was most likely a scam, so she did not pursue it.”

But Moonen persisted, and contacted another daughter, Pamela Peterson, who was persuaded to give him their father’s phone number in Sun City.

Archeology student Bart Moonen reunites the late John E. Throckmorton with his WWII Army dogtag at his grave in France. (Thanks to Frank Geister and the Sun City Computer Club for help in obtaining this photo). (Photo Provided)

“I got Martha on the phone, and she was quite understandably skeptical about the story that I was telling,” Moonen said. “After some persuasion she let me talk to John F., who was also skeptical, but we exchanged email addresses so that I could explain the situation and that I was doing this with good intentions. Our conversations helped to clarify a lot to them.”

Bart and Ivo visited John E.’s grave in Lorraine, France, and briefly reunited the fallen soldier with his dogtag. They hung the tag on his grave marker, and recorded the event, as they do all their excavations. They then shipped the tag to John and Martha in Huntley.

Bart and Ivo traveled to New Orleans this past June and met and joined John F. and Martha at the division’s 2013 reunion. Bart and Ivo’s extensive videos of their digs in Germany, including the discovery of the tag, can be viewed on the association’s website.

“After talking to Bart and verifying that this was not a hoax, we were stunned and very emotional,” John F. said. “It was amazing that they accomplished this and worked so hard to tell us about it.”

“We presented our story to the association members, and we went to dinner together with the Throckmortons,” Moonen said. “It was very nice to meet them and a little emotional. In the end, all the hard work and research paid off in the gratitude I received from the Throckmortons. I think I owe that to the sacrifices made by the people that fought for the freedoms that I enjoy today.”

19 Comments

To the mysundaynews.com admin, Your posts are always well-structured and logical.

Hello mysundaynews.com owner, Keep the good content coming!

Hello mysundaynews.com admin, Your posts are always well-structured and logical.

Dear mysundaynews.com admin, Your posts are always informative and up-to-date.

Dear mysundaynews.com owner, Your posts are always insightful and valuable.

To the mysundaynews.com owner, Thanks for the well-structured and well-presented post!

Dear mysundaynews.com webmaster, Your posts are always informative and well-explained.

To the mysundaynews.com webmaster, Keep up the good work, admin!

To the mysundaynews.com owner, Thanks for the informative and well-written post!

Hello mysundaynews.com administrator, Excellent work!

Hi mysundaynews.com admin, Your posts are always on point.

Hello mysundaynews.com owner, Nice post!

Hello mysundaynews.com webmaster, Your posts are always informative.

Dear mysundaynews.com webmaster, You always provide helpful information.

Dear mysundaynews.com admin, You always provide great resources and references.

Dear mysundaynews.com admin, Thanks for the informative post!

Hi mysundaynews.com administrator, Your posts are always well-timed and relevant.

Dear mysundaynews.com webmaster, You always provide valuable feedback and suggestions.

To the mysundaynews.com administrator, Thanks for the educational content!