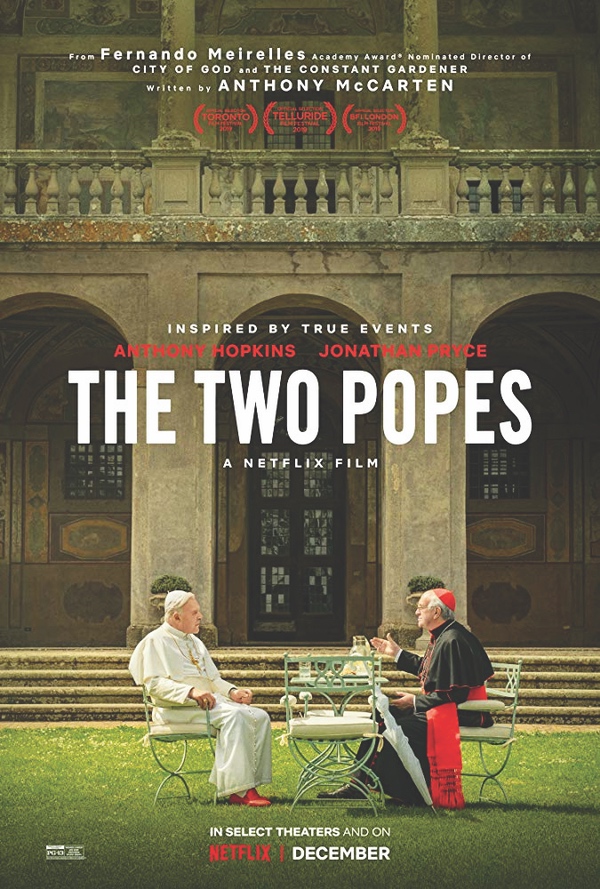

“Living together is an art. It is a patient art, it is a beautiful art, it’s fascinating.” — Pope Francis

There is nothing more insufferable than a filmmaker who doesn’t allow their movie to breathe, to let us come to certain conclusions naturally. A director inserting themselves into their film, not literally but through their style, is the biggest crime that they can do for their audience. Mostly this is said of flashier action films and big-budget blockbusters the likes of Michael Bay and J.J. Abrams. But sadly this can also be found in smaller art-house films; the works of Lars von Trier and Gaspar Noe come to mind. This same can be said of Fernando Meirelles and his latest for Netflix.

For starters, let’s get the good part. Much speculation has been had about why Anthony Hopkins and Jonathan Pryce were nominated at all for these roles. After seeing them, I can see why, but not in the way most would think. Yes, this is the typical work you would see from any standard biopic. Pryce gives a warm, self-assuring grace to the future Pope Francis. His smile could melt glaciers. But he can also present his darker side with deep pathos, giving him layers that don’t just serve as history or backstory but of a life lived fully. Hopkins, by contrast, is world-weary the moment we see him. A man entrenched in traditional values that he doesn’t even greet Francis at the conclave to elect Pope John Paul II’s successor. Actors such as these are in ways rather independent of the person behind the camera. Their verbal sparring matches are electric just on their own, but are marred by the director.

The Two Popes

Rating: ★★

Directed by Fernando Meirelles

Starring Jonathan Pryce and Anthony Hopkins

Meirelles has been kind of a wild card over the years. He came onto the scene with the excellent “City of God” however ever since I have not known what to make of him. The adaptation of John le Carre’s “The Constant Gardener” showed that his style doesn’t really translate to all of the subjects he is given. His following film based on Jose Saramago’s novel “Blindness” was baffling to say the least. Ever since he has been shuffled from fewer and smaller projects. It’s no wonder why Netflix is able to snatch him up.

At the beginning his use of handheld documentary camera works in the street scenes leading to Cardinal Bergoglio (Pope Francis) seem like a nod to “God.” But then he abandons it…and goes back to it. Where this would work in a more action-driven film, this back and forth becomes jarring. In a scene where Bargoglio meets with Pope Benedict to tender his resignation, we are treated with an overhead shot of them entering a garden. Why Fernando? For what purpose is this here then to have us notice your direction? Flashbacks are cut into the movie with no narrative flow, using different color pallets to reflect different points in Francis’ life to no affect because we are given the place and time onscreen. What is the point of this? Without these stylistic choices we are clearly just watching a two-man stage play.

After the movie, I was glad to see that I was right upon some research. The script by Anthony McCarten was adapted from his play. It would be intriguing to read the actual script to see how faithful the visuals were to the staging. One of the best scenes between Hopkins and Pryce happens in the Sistine Chapel which is certainly mocked up in impeccable fashion. Kudos to the production team for that effort. However it is wasted with the documentary framing. What this could have used was a more deft hand and fluid camera movement the whole time. Maybe Stephen Frears whose work on “The Queen” could have complemented the stagy script while making it more cinematic. Or maybe the new Italian directors would have been better suited for this material. Paolo Sorrentino’s Oscar-winning “The Great Beauty” and HBO’s “The Young Pope” proves his dreamlike eye for mixing the real and surreal has validity. Or Luca Guadagnino’s more natural unobtrusive camera in films like “A Bigger Splash” and “Call Me By Your Name” would have made the scenes more intimate and intense without relying on the score. He would certainly have made that overhead shot better integrated.

Speaking of the score, this was the icing on an already poorly baked cake. Bryce Dessner has been more of fixture in the rock world than in the classical one where he has inserted himself. He matches the direction; one moment using Latin guitar, the next composing sustained strings that are supposed to be suspenseful for scenes where we know what is going to happen. This film is the equivalent of a parent jangling keys in front of a child’s face. It is all neither patient nor fascinating.