April 8 was quite a momentous day for the nation. Hopefully, dear readers, you were able to catch even the minute of glimpses. A thunderhead came over the skies as our beloved moon fell into orbit, just transiting our sun. That star became like obsidian to some, varying degrees of shade for others. Vacationing in Indiana, I was able to witness ninety-eight percent coverage from the comfort of a lake house, bloody Mary in hand. Although not complete totality, the sight was beautiful just the same. Sudden shadows and birdsong transfixed me as the extremely waning crescent hung above us; an eerie experience indeed, but gorgeous as well.

That may also be the best way to describe Netflix’s latest sensation Ripley. This is the third attempt at adapting Patricia Highsmith’s labyrinthine novel. But this has to be the murkiest. Having went to the theater in 1999 to watch the Matt Damon version, director Minghella’s light touch brought us into lush hotels and rivieras regardless of the proceedings. It may have even brought about my love of jazz. Later I found appreciation for the 1960s French take starring Alain Delon, his suave demeanor oozing sex appeal across the screen.

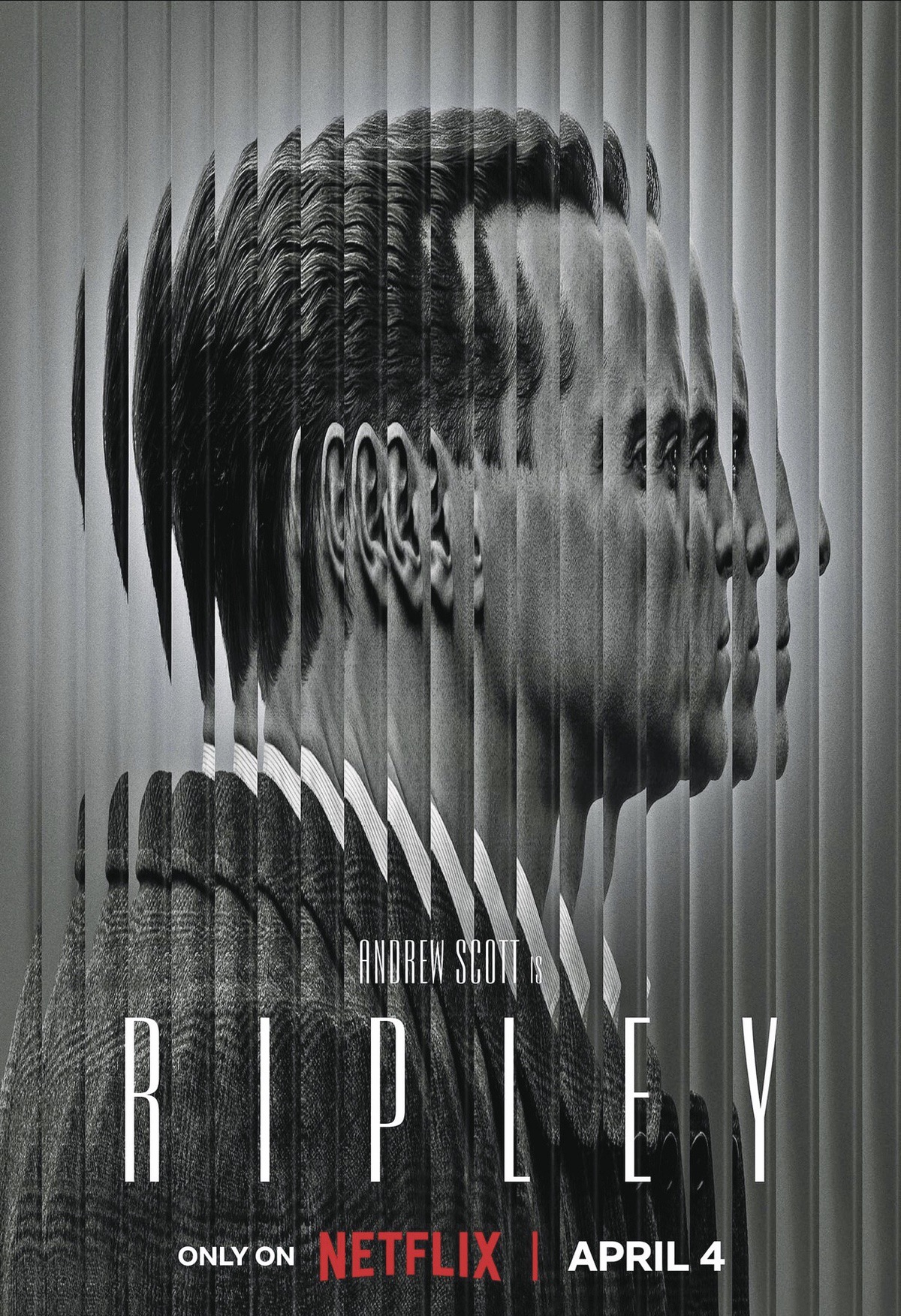

Fresh off All of Us Strangers (and Hot Priest from “Fleabag” for some), Andrew Scott finds yet another facet in this prism of a character. Tom’s awkward body movement and facial expressions hide any true nature in the opening episodes. Is he just socially inept or unable to completely obscure his more dangerous tendencies? A smile can be just mechanical, functional; lacking any empathy. Yet he knows what to observe and use to his benefit, secure in his scheming. When we find him in New York, scams are as natural as breathing to him. When Mr. Greenleaf extends Tom an invitation to bring his son Dickie back, he jumps at leaving for Europe.

One thing immediately different; the black and white photography, though lacking in vibrancy, lends austere grandeur to Highsmith’s tale. Writer/director Steven Zaillian has claimed in interviews that choice was due to a photo on his hardcover copy. But Robert Elswit’s monochrome, not unlike his work in Good Night and Good Luck, isn’t grainy nor lacking in texture. Whereas there, it was about expressing gravitas towards journalism. Here, it obscures Ripley and his underlying motives. Detailed focus on surroundings either lit or bathed in dark silhouettes, he evokes Ripley’s beloved Caravaggio paintings. The stilted acting, which could get annoying, only delves further into Tom’s twisted mind. Through imaginary conversations and expository letter reading; this is Tom’s story no one else’s.

Johnny Flynn is commendable as Dickie as is Eliot Sumner as his pal Freddie Miles. The MVP would have to go to Dakota Fanning as Marge Sherwood. Her deadpan delivery becomes much more engaging coupled with each flit of her eyelash or slight curl of a smirk. No emotion is left unpunctuated, nor devoid of nuance. She can go toe-to-toe with anything Scott throws at her, an adversarial tango by the last episode.

A dark sense of perverse humor is peppered around, as characters are forced to walk innumerable flights of stairs or as Ripley bungles through disposing of bodies, never a dull moment for anyone into more arty fare. Only one complaint I have is the more obligatory call-backs to previous Ripley films. A stray reference in the music here, a minor motif there is all well and good. Casting John Malkovich in a meta-conversation about art dealing was an exercise in fourth wall breaking I thought reserved for Tarantino. Nevertheless, Netflix is to be commended for presenting such a masterful bauble of a miniseries; fit for a night with some red wine and fun company. Just be careful to whom you make those friendships with.